Docker for Java Developers - The Big Picture

19 Jan 2017Introduction

The Docker train has already left the station and people are thinking if they should jump on it or not. It is true that Docker adoption is unprecedented compared to other technologies that were hyped before it.

Getting quality information on what Docker can do for you is surprisingly very difficult. At the time of writing, most Docker articles and posts on the web fall under the following categories:

- Official documentation that explains how things work, but not why and when you should use them

- Company sponsored articles from companies that are selling solutions on top of docker

- Very simple hello-world tutorials that (at least for the Java crowd) are not really that impressive

- Docker opinions from people who have used Docker in production to solve some very specific problems (that might be different than yours)

- Very short articles that present fancy pictures with real world containers and explain that Docker is the next best thing since sliced bread

Another issue with several Docker articles is the elephant problem. Since Docker touches so many areas (development, continuous delivery, operations), a lot of articles only view Docker from a specific standpoint and never explain the big picture. For example, monitoring and debugging Docker containers is very conveniently left out from a lot of articles (implying that this is a trivial problem)

It is also very hard to find language specific information for Docker. I can understand why Ruby and Python developers are excited about Docker, but in the Java world where good specs already exist, some of the Docker advantages are not that ground breaking. (As a fun exercise, even if you are a Java developer, try to find installation guides on how a Ruby on Rails application is deployed in production)

Finally, the Docker train is following/leading the Microservices train. Several articles confuse the two together even though they are completely independent. You can use Docker with a monolith app, and you can have several micro-services without using Docker at all. In this article we will just focus on Docker (this time around!).

Target audience

The aim here is to look at Docker through the eyes of a Java developer. We will examine in a much more objective way if Docker can really help you and we will attempt to de-hype the Docker craze.

First let’s get this out of the way:

If you work in a pure Java shop and you already have the perfect build system based on VMs and everybody (developers, testers, operations) are happy, then adopting Docker is indeed an open question. You have to consider the possibility that Docker will do more harm than good in your organization (at least in the initial adoption stages).

So don’t feel bad if you read about Docker and just don’t seem to grasp why everybody thinks that it is the only way going forward. This actually means that your organization has reached a high level of operational maturity. Despite what Docker evangelists say around you, there are several stages for Docker adoption and you are free to stop at any of them rather than doing all things the “Docker way”. More on this later.

In fact, a major Docker disadvantage that nobody talks about is that Docker is OS specific. Most Docker images are targeted at Linux, and only recently Docker has appeared on Windows. But (unless you use a VM) an OS runs only its native images, Docker on Linux runs only Linux images and Docker on Windows runs only Windows Images. Sad but true.

This is a step backwards from the Java world (compile once - run everywhere) where the exact same WAR file can run equally well on Windows, Linux and even MacOS. If you have a Java product that for some reason needs to be deployed on multiple OSs at the same time, then migrating to Docker is a questionable decision.

Let me repeat that last sentence. Compared to the JVM which is OS agnostic, Docker is a step backwards and you should be highly skeptical when thinking about moving your Java apps to Docker images if that compatibility matters to you.

The source of Docker confusion - the name itself

Understanding what Docker does is becoming even more difficult because “Docker” today is actually an ecosystem. When people around you talk about Docker you should understand what part of Docker they are talking about. The company? The container? The format? The CLI?

Just to help you get around all this confusion I have created a table that attempts to map all Docker concepts in the Java world. This table is not technically accurate as some technologies work differently under the hood. It is just here to give you a fuzzy idea on how things match.

| Docker Term | Description | Java world |

|---|---|---|

| Docker | The company | Oracle (previously Sun) |

| Docker image | The image format | WAR file |

| Docker Engine | The runtime | The JVM |

| Docker Container | The container | Tomcat/Weblogic etc |

| Docker client | The image creator | Maven/Gradle |

| Dockerfile | The image definition | pom.xml/build.gradle |

| Docker client | The image runner | Weblogic CLI/Tomcat/Gradle scripts/ Maven plugins |

| Docker compose | Grouping Docker images | EAR file |

| Docker hub | Image repository | Maven central, JCenter |

| Docker Registry | Private image repository | Artifactory/Nexus/Archiva |

| Docker Machine | A VM with Docker installed | A VM with Tomcat installed |

| Docker Swarm | A cluster solution | Many proprietary Java solutions |

You can see instantly why “Docker” is such a confusing term and why it means so many things to different people.

You now have the power to understand what exactly people are talking about when they mention Docker. Spend 5 minutes on probing questions until you are certain that you know what part of Docker they refer to. Knowing this information is important as you will see later on.

It is interesting to note that Docker has actual competitors in most of its product line. The biggest one as far as containers are concerned is RKT.

Docker (the company) is moving to a standards based approach (see runc and containerd), creating specs for several critical parts of the whole ecosystem. Whether that will lead to a world similar to JavaEE remains to be seen.

Docker considerations for the Java developer

The comparison table above should already save you a lot of time. Now every time that you read a Docker article and it starts talking about this magic way of “creating self-contained archives that include all application code”, you can just shake your head and move on (as the article is probably not targeted at Java developers).

In a similar manner, if a Docker article talks about how you should “push your Docker image to a repo and then pull it at a later pipeline stage”, you should laugh, as this is the only valid way to run a proper continuous delivery organization (and you should be doing that already).

In my experience, people outside the Java ecosystem are first impressed with Docker - the image format, and secondly with Docker - the container runtime. They almost always assume that Linux is used both in production and in development (something that is not always true in the Java world). The idea that the same Docker image is used both in production and in development is something unique in their eyes (because they are unaware that this was already a reality in the Java world even before Docker).

Despite what Docker zealots tell you, as a Java developer you really need to see Docker as a lightweight VM technology. They are correct in the sense that Docker is NOT a lightweight VM technology. However, most of its advantages could be matched if we somehow magically could launch lightweight VMs in less than a second. Alas we cannot, and this is why Docker is gaining ground.

If your existing VM infrastructure suffers from speed, then Docker indeed can help you. If however, VM speed is not essential to you (and your existing issues are completely different) then a possible Docker adoption needs a very carefully planned evaluation phase on your part.

In particular, if you are a heavy JavaEE user and your application is a single WAR/EAR file that gets deployed on Weblogic/Websphere and uses a big bulky Oracle DB, I would advise you to stay away from the Docker craze until you are fully certain that you understand the implications behind adding another level of complexity in your organization.

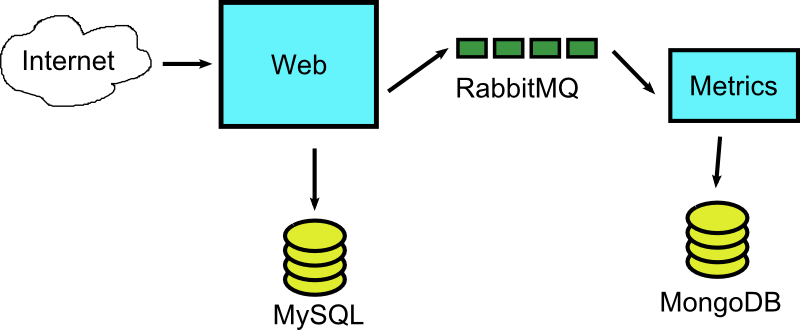

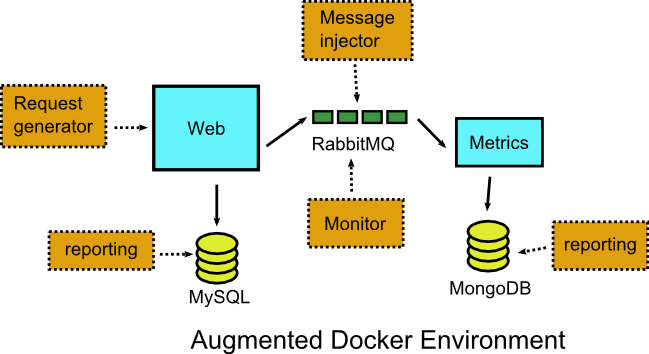

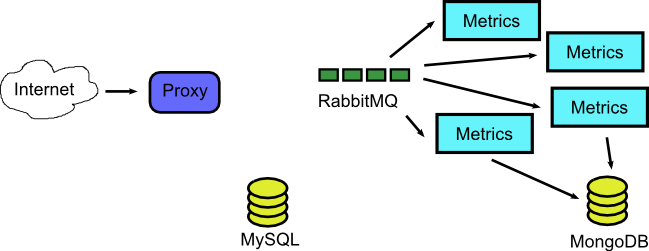

So with that in mind let’s see some tangible advantages. As an example application we will assume that we have the following components:

- A Java application that implements a Web interface and accepts customer orders

- A Mysql DB that is used for main storage

- A second Java application the creates reports and records metrics

- A Mongodb for keeping metrics

- A RabbitMQ instance for communication among the two applications.

Here is the diagram

So let’s see what Docker brings into the mix.

Advantage 1 - Running integration tests on developers’ machines

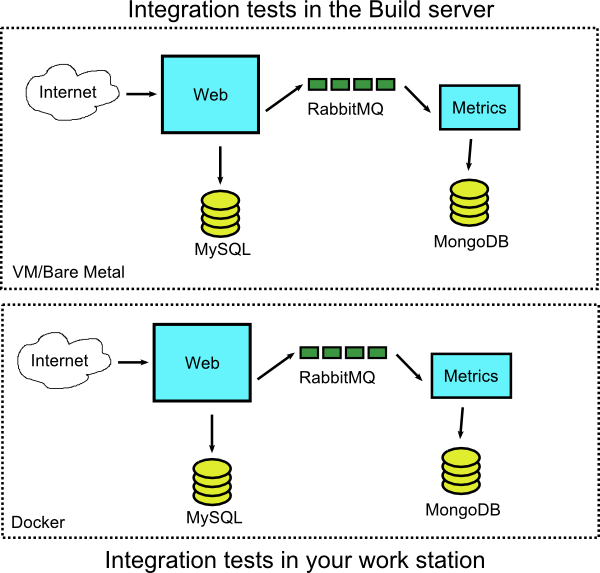

The first advantage and my recommendation for starting with Docker, is to attempt to Dockerize your application in your workstation only. This means that with Docker Compose you should be able to replicate the full running system in your own workstation/laptop. As a baby step you could also try to just dockerize your application without the DB (i.e. Oracle) and see how this goes.

Normally, before you commit a piece of code you need to make sure that it passes all test suites (unit, integration, functional, acceptance). In practice however, developers just run unit tests locally and then assume that integration tests will be handled by the build server at a later stage.

Ideally you want to have the shortest possible feedback cycle and instead of waiting for the build server, have the ability to find problems before they are committed. Even if the integration tests take a long time, you should be able to run only a subset of them to verify that nothing is broken in your local workstation.

Docker gives you the ability to setup the complete environment locally and re-run the same integration tests the build server would perform after your commit.

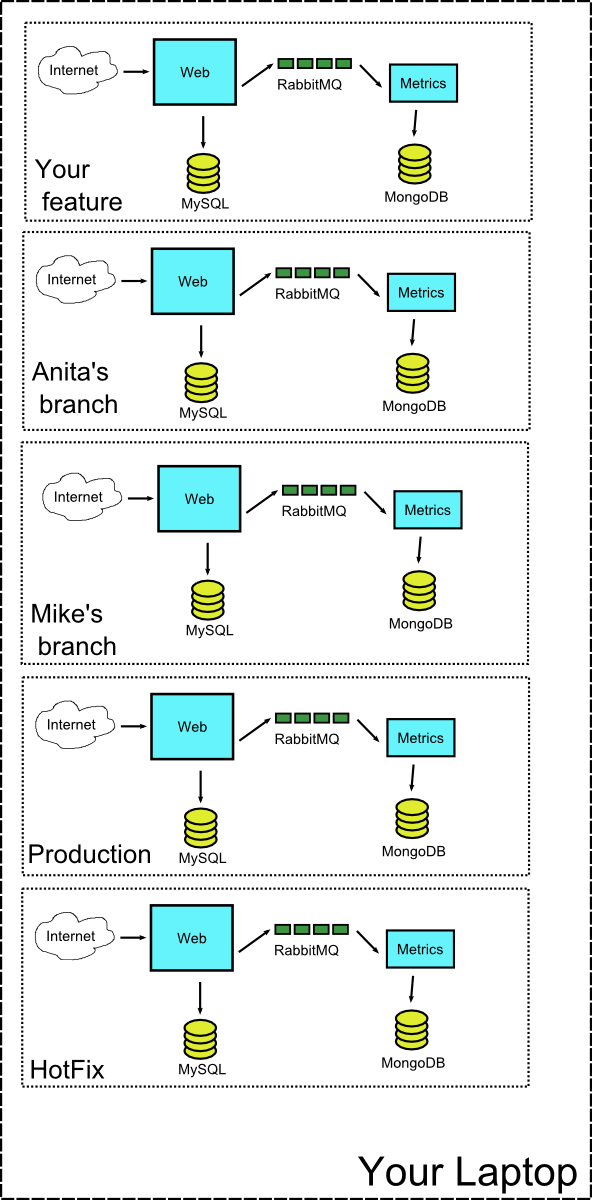

Of course you also achieve the same effect by running a VM locally that contains all components of the system. But because Docker does not take as many resources as a VM you can extend this idea to run any number of complete environments at the same time. Previously your workstation might be able to run 2 or 3 VMs at the same time, but with Docker you can run 10+ containers with similar complexity.

As an extreme case you could launch at the same time using Docker containers

- The feature you are working on now

- The branch from your colleague Anita that is ready for code review

- The branch from your colleague Mike that presents some unexplained exception

- The production version of the system for load testing

- A hotfix version for locating some important bug

Having a large number of VMs running can quickly overwhelm a single workstation. With Docker containers however, this becomes a possibility.

You can run integration tests for all that environments at the same time keeping everything neat and isolated. Having multiple environments running in tandem is especially useful when you are comparing their behavior (you have found an unrelated bug in a branch and you also examine if it is present in the current production).

Advantage 2 - Debugging applications locally

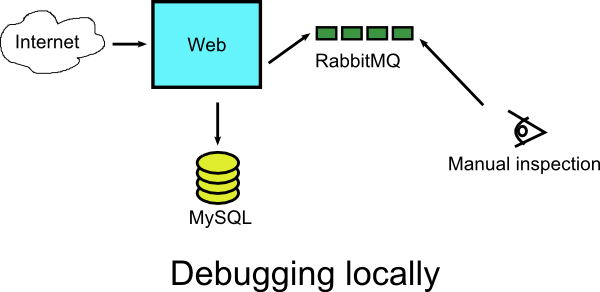

The previous section talks about using Docker locally before a commit goes to the production system. The reverse ability is also very useful. You can use Docker to attempt to identify problems after they have happened in production.

Usually what happens in such cases is that you will try to reproduce the issue locally in order to understand why and how it happens.

If you are lucky, the problem will be evident even if only a part of the real system is actually live. This allows you to just launch a subset of the whole application locally instead of having to deal with the whole configuration.

In our example application let’s say for the sake of argument that the metrics application is very complex to setup locally. It uses special configuration files that makes its local deployment really difficult.

Let’s say that an issue appears when invalid messages are sent to RabbitMQ by the main web application. You could potentially only startup the main application, its DB and the RabbitMQ cluster and do not use the metrics solution at all. Then you could retrace the events that happened in production and just examine manually what messages reach the queue. This would save you from launching the metrics application locally, which is a compromise since you don’t have the full picture of what is happening in all parts of the system.

Unfortunately there is a very sneaky category of bugs that happen only under specific versions/configurations. The first thing that comes in mind is issues with things like line/path delimiters where the production system is running on Linux, while developers run Java application on their local Windows workstation. The second thing that comes in mind is incompatibilities among Linux distributions. Your developer machine runs Ubuntu, the production server runs Redhat and and several OS libraries are different between them making the replication of the production environment very difficult.

In that case it is best to replicate the whole system at the OS level locally. And yes, a VM could also achieve the same result, but as explained in the previous section Docker containers are much more flexible and efficient.

I have also seen companies where there is no such thing as one production system. Each customer has a similar (but slightly different) version of the production code, so isolating everything with separate Docker containers is much easier.

With the help of Docker filesystem layers and Docker compose it is very easy to “enhance” the production system with extra debugging utilities and tools.

In our example application, you would easily create a special Docker deployment that “extends” the integration test environment described in the previous section and includes an extra debugging application that connects to RabbitMQ and monitor/dumps/filters messages

Advantage 3 - Creating test environments on demand

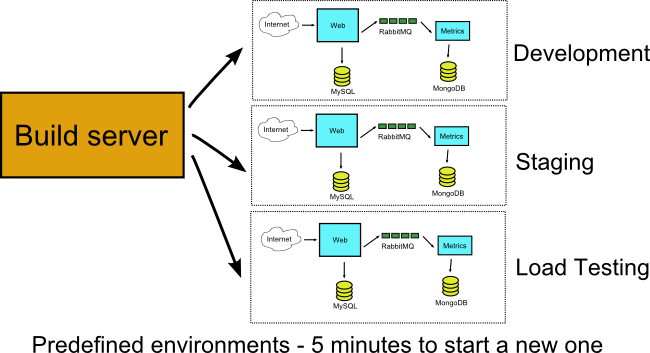

Having mastered Docker locally the next logical step is to use it in the build server of your organization. Just to be clear however, I am not talking about powering the build server itself by Docker containers (more on this approach later in this article)

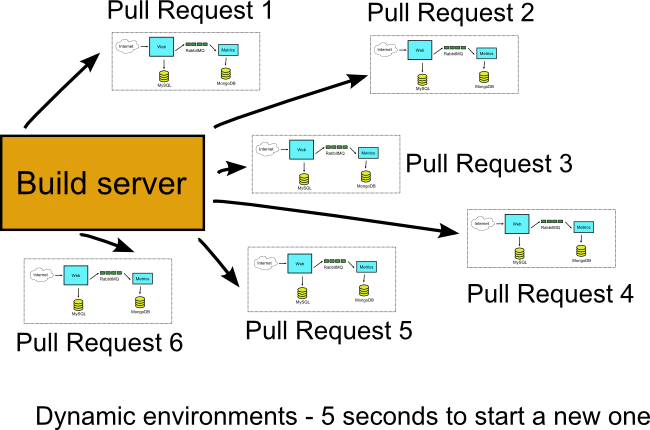

If you have already dockerized your application locally, then the build server should be able to do this automatically for each feature branch. Ideally each pull request should get its own environment.

This is one of the simplest ways to move your organisation from continuous integration (each feature branch is compiled after every commit) to continuous delivery (each feature branch is compiled and deployed after every commit)

The important thing here is to abandon the practice of having multiple pre-defined VM environments (i.e. qa, staging, live) and instead have the build server create any number of deployment environments when needed. If at some point in time for example six people in your team create six pull requests, your build server will create six individual (and completely isolated among them) Docker environments with no human intervention.

If your VMs already do this, then you are fine and Docker will not bring anything new to the table apart from speed. If however you have issues where build jobs compete for the same predefined environments, it means that Docker will help you with their isolation.

The classic symptom for lack of isolation between pre-existing test environments is having unstable integration tests, that fail or succeed depending on which other job uses the same deployment environment.

Advantage 4 - Stateless to the extreme

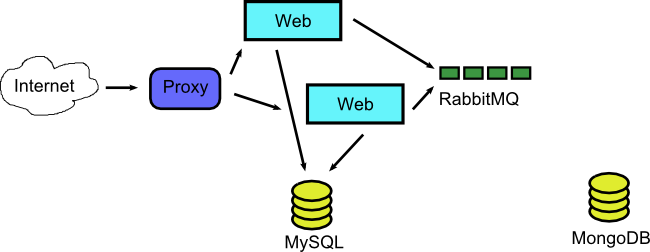

A unique advantage offered by Docker compared to VMs is the possibility to use it in places where VMs would fall short right away. Most people think about Docker advantages in the context of deployment and testing but in reality Docker could also play part in your overall system architecture.

This aspect of Docker is not examined yet in detail, so please - please be very careful if you go down this route. In our application example we could discard our static architecture and go for a fully dynamic one where a Docker container is created per request. This is a something that a VM could never pull off.

So we start our system with just the two DBs (and possibly a proxy/balancer/dispatcher) and then we monitor requests and RabbitMQ messages and launch Docker systems in place for each individual message. Let’s say that two requests come that request a web page.

The docker containers that served the requests have finished and are teared down. Their processing result created 4 messages for the metric application. So we launch dynamically four respective containers to serve these messages.

Once all processing is finished the whole application reverts back to the original state where no Docker containers are running at all.

This is an extreme case of how fine-tuned scalability decisions we can take with Docker. Of course there are several auto-scalability mechanisms for VM based applications, but these work at a much broader context.

At the time of writing, Docker documentation on this matter is very limited, possibly because most people are simply exploring Docker in the deployment level rather than the architecture level.

Of course it should be obvious that by following such schemes, your application architecture becomes tied with Docker itself so be aware of the risks involved. It is best to start with Docker as an extra layer in your architecture before integrating it into the architecture itself.

Advantage 5 - Working in a polyglot organization

I left this advantage for the end because even though it is one of the most advertised features of Docker, it is not that visible in Java shops.

If you work in an organization where Java is just one of the many languages used in production, then adopting Docker will indeed make communication much easier across all teams. People from operations will no longer need separate lengthy installation guides for Ruby, PHP, Java etc. Instead they will focus only on Docker.

Docker will become the universal deployment method allowing operations to specialize on a single technology regardless of the underlying implementation. This is obviously a big argument in favor of Docker if several programming languages are used in your organization.

If you are working in a pure Java shop however, this is a non-issue as your operations people should already be accustomed to WAR/EAR files. Yes, Docker might provide some extra features but a well-oiled operations team will have already streamlined the deployment process with custom scripts.

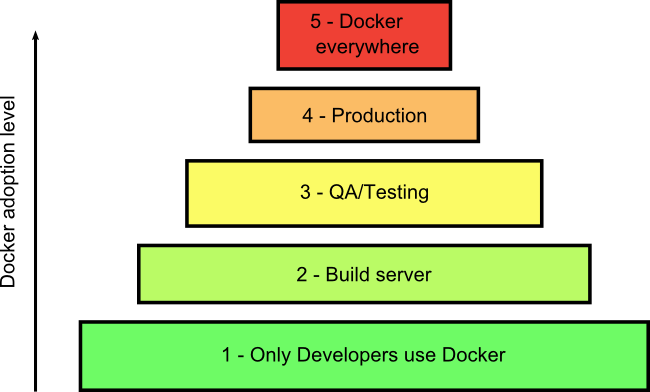

Docker adoption stages

We now reach the most important point of this article. You can choose how deep you will integrate Docker in your organization. There is no straight route to Docker nirvana. There are many stepping stones and you are free to choose your own pace.

Here is the overview of Docker adoption. I have designed each step as an absolute prerequisite of the next one, because this is my own recommendation on how you should approach Docker.

I have already hinted at these adoption stages in the previous sections, so let’s see them now in detail.

Before going up to the next adoption stage, you need to decide the trade-offs and implications. It is perfectly fine to stop at any adoption stage in between and never reach level 5.

My motivation behind this present article is to make clear that each adoption level can stand on its own. A lot of Docker articles jump straight to stage 5 and never explain the fact that your organization can function perfectly fine in stage 3 (or even stage 2 for that matter).

Adoption Stage 1 - Only Developers use Docker

Stage 1 is essentially an evaluation of Docker that will show you how many changes you need in your application. If you are developing with certain frameworks (e.g Spring boot) you might find that it is easier to use Docker but not all organizations are that lucky (i.e. those that depend on many JavaEE specs).

At this stage you (the developer) can focus only on Dockerizing your application for your own local use. There are several Docker related topics that are simply irrelevant if you only use Docker locally. Don’t let neighboring technologies distract you.

The advantages from this stage are two fold:

- You have an initial evaluation on how easy is to convert your application to a Docker image

- You have the ability to run multiple environments locally (without tampering with application server ports and other hacks)

At this first stage you only need with Docker and possibly Docker compose. There is no need to concern yourself with Kubernetes or Docker swarm (these bring their own idiosyncrasies) at this point in time. I am always amazed by the number of articles that imply Kubernetes is an essential component of any Docker based solution.

If your organization has a good VM architecture that runs like a Swiss clock in both testing and production phases, then staying at this initial stage of Docker adoption is perfectly fine.

You should never move to the next adoption stage if there are still blurry areas on how your application can play well with Docker.

Adoption Stage 2 - Docker enters the build server

With the experience of running Docker locally you are now ready to let the build server take over (so that complete deployment environments can be created per feature branch).

This is not a straight-forward process if running Docker locally required several shortcuts. While you may be comfortable executing multiple statements in your command line, the build server process must be completely automated and streamlined.

The most common problem here is configuration management. Creating isolated Docker environments means thats each one does no clash with the other in any way (i.e. writing to the same files or using the same DB).

Depending on your situation it is sometimes acceptable to reuse some infrastructure among your environments (for example your email server).

You need to make sure that all the following topics are addressed

- General configuration settings for each environment

- Confidential information, secrets, optional encryption/decryption keys, code signing

- Ports and network arrangements

- State of your application (DB, files, sessions)

The final outcome of this stage would be that any number of completely independent environments can be created in your build server using the same Docker image.

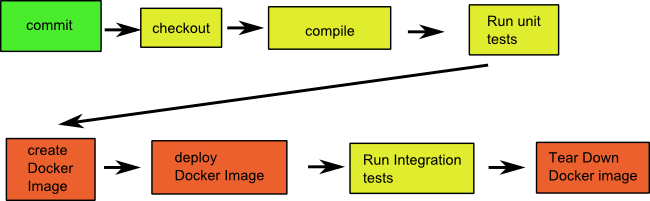

At this adoption stage all Docker environments created are short lived and exist only for running integration tests against them. The full process is the following:

- You commit something on a feature branch

- Build server notices the commit and checks out the branch

- Build server compiles code and runs unit tests

- Build server creates a Docker image

- Build server deploys Docker image

- Build server runs integration tests against the Docker environment

- Build server tears down Docker image and creates a report.

Notice that it is perfectly fine to use Docker environments for pull requests and still have pre-defined VM based environments for testers. You can mix both strategies at the same time.

It should be clear that even at adoption stage 2 Kubernetes is not a strict requirement.

Adoption Stage 3 - Docker is used for Testing/QA

Having mastered short-lived Docker environments visible only to developers, it now time to present Docker to testers as well. The goal here is to remove all predefined VM based environments (qa, staging etc) and replace them with long-lived Docker containers.

Keeping Docker containers running is a huge topic on its own. While in theory you could use plain Docker and nothing else, it makes sense to start researching orchestration solutions (i.e. Kubernetes) now. Even if your testers are not that picky as your customers (and they can accept some downtime), knowing how to keep Docker containers alive is a prerequisite for the next adoption stage.

At this stage you should also decide how deep Docker will be used in the application.

- Will you dockerize just the application code and leave the DB outside?

- Will you dockerize the mail server? The queue? The cache?

There is no right and wrong answer here. There is a tradeoff between the size/complexity of a Docker image and how self-contained it can become. A common Docker migration path I see is the following:

- Developer learns about Docker and gets excited with the “put all dependencies in” concept

- Developer creates a single Docker image (kitchen sink approach) that results in a humongous file size

- The Docker image is very slow to create, very slow to copy and very slow to build

- Creating/Running the Docker image is non-deterministic and produces different results each time.

- Developer is questioning the Docker adoption and the JAR approach seems much more favorable now

- Developer finally starts reading about the Docker file layers, the idiosyncrasies of Docker files, caching strategies/ image repos and image cleaning tools.

Of course the correct migration path is to start from the last step (understanding the implications and tradeoffs of Docker) and then actually start creating images.

Another area that you need to research at this stage is how to get metrics from your Docker containers. Your logging strategy will almost be refactored as well.

Still, because Docker images are used only internally by your organization you have a certain amount of slack to try and experiment without the fear of tampering with production systems.

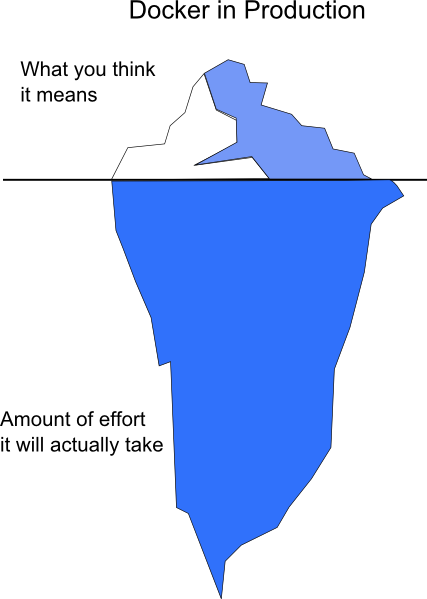

Adoption Stage 4 - Docker is used in Production

This is the point of no return. Assuming that Docker is already being used in your own testing systems and everybody is happy about the way things work, it is time to unleash the Docker potential to your customers.

This adoption stage is special because there is a great deal of preparation that is involved before mastering it. Things that were optional (e.g. orchestration) in the testing stage, are strict requirements in production.

Here is a partial list of things that you need to sort out before using Docker in production.

- Gathering of performance metrics

- Using Rolling updates

- Ability to revert deployments

- Security isolation

- Management of secrets

- Handling environment configuration

- Setup of networking/load balancing

- Live monitoring of business indicators

- Image/Binary management

- Continuous delivery and build workflow

- Logging

- Provisioning of resources

- Resource limiting

- State handling

- Debugging/Hotfixing

- Clustering/high availability

- Auto-scaling

- Keeping backwards compatibility

- Managing backups

These topics are even more concerning if you run applications on premises using your own data center. Admittedly if you use a cloud provider some of these issues might be taken care for you already. Even then, you should be aware on the tools/dashboards offered and how you can employ them effectively.

If you have been paying attention you should see that the list above is not Docker specific. My point here is that using Docker in production requires essentially a rethinking across all your existing practices.

Adoption Stage 5 - Docker is used for everything

If you are a startup or a company that uses a public cloud for its operations, then Docker adoption stage 4 is as far as you can go.

If on the other hand you have a datacenter and/or a private cloud, it might make sense to go a bit further and Dockerize everything. This is the Docker nirvana stage.

If you have managed to use Docker in production for your own application (and things work smoothly), you could attempt to run all your applications with Docker as well. This will allow you to have a single deployment architecture for all applications regardless of their source.

You can start by Dockerizing the development infrastructure itself by using containers for:

- The source code repository

- The build server

- The Binary repository

- The image repository

- The issue tracker

- The wiki

- The code review application

Why stop there? You can keep going and use Docker for your CRM, your warehouse inventory, you email server, your invoice formatter etc.

Of course, if you are a small company that uses several applications on public cloud, this may not be an option. If however, you actually have a physical datacenter, then there is no point in managing two infrastructures (one for your internal applications and one for your own source code). It should be much more cost efficient to unify them and use Docker containers for the whole datacenter.

It goes without saying, that before attempting this strategy, you should consider yourself a Docker guru. Accepting downtime for your QA environment will be much different than accepting downtime for your CRM.

Conclusion

I hope that with this article you have a better idea on what Docker means for you (a Java developer) and when it can help you. Here are the key points:

- People outside the Java ecosystem are dazzled with Docker because it embodies a deployment “spec” for them. You should understand now why they are so excited about Docker (because it solves problems the Java world simply does not have).

- If you are happy with your existing VM operations, then switching to Docker is a decision that needs a lot of consideration, and at least for Java developers, the advantages of Docker are not that ground-breaking.

- If your Java application needs to be OS agnostic then most certainly Docker is not a good idea

- Docker adoption is a multi-stage path with several intermediate phases. Feel free to stay at any phase and get comfortable before moving on to the next.

- Using Docker in production is not something that you should take lightly. Make sure that you have mastered Docker deployments in your testing environments first.

- In reality most people who run Docker in production, run it on VMs anyway, so by adopting a Docker strategy you are essentially adding a complexity layer instead of replacing VMs with Docker (as many people falsely advertise).

Finally, the next time a Docker fanatic comes to you and suggests that you should start your Docker journey by converting your physical Jenkins server to a Docker image you should explain to him/her that you want to slow down, take a step back and re-evaluate the whole situation before starting a company-wide level 5 Docker integration. Don’t let the hype consume you.

Go back to contents, contact me via email or find me at Twitter if you have a comment.