Using Spock to test Groovy AND Java applications

28 Feb 2013This post was originally published at the JRebel/Zeroturnaround blog. Reposting here since it is not available there any more.

Introduction

When it comes to Java, most developers either use JUnit or TestNG. JUnit is the established de-facto solution, while TestNG attempts to offer additional features needed for Enterprise applications.

For excellent unit tests, you also need to looking into mocking as I explained in one of my previous posts. For this need Mockito comes to the rescue and offers powerful mocking abilities to your unit tests.

So is JUnit/Mockito the best possible combination?

For this post, I took some time to play around with another testing framework called Spock. Spock is a test framework for Groovy applications, however as a Java developer I wanted to know how well it did at testing Java code as well.

Spock is stable and solid (it has been around since 2008), even if at the time of this writing, it has not even reached its 1.0 release. But it has some interesting features that you might find beneficial for testing your Java & Groovy apps, like how Spock can perform both assertion checking (like JUnit) and Mocking (like Mockito) at the same time. So, now you have two libraries in one! How cool is that?

Getting Started with Installing Spock

Unfortunately, the reference documentation for Spock is not yet ready. So the Getting started page in the old Wiki is not up-to-date, since most of the effort is going to the new Documentation.

There are multiple ways to use Spock. Some of them are:

- As part of a Gradle build (which is Groovy’s build tool of choice)

- In a Maven project (which can have both Java and Groovy code)

- In an Eclipse project

- On the web with no installation at all. See the Spock console.

The old Wiki still contains descriptions about old versions of both Spock and Groovy. In the end, I chose the Eclipse way.

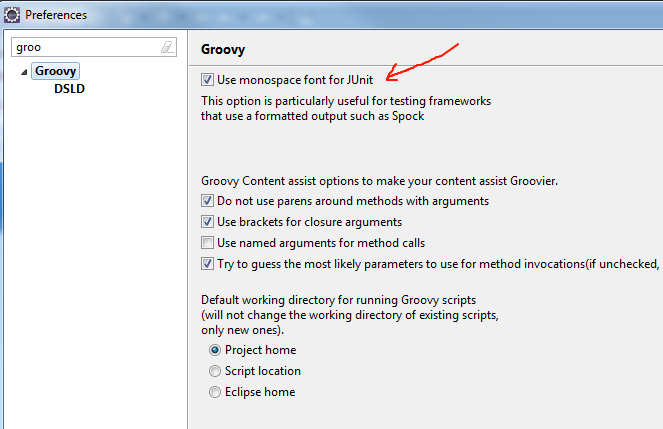

There is a Groovy plugin on the Eclipse MarketPlace that adds support (syntax highlighting, code completion) for Groovy scripts, so once you have it installed you are good to go. Protip: Make sure that you select the “monospace font” option in Eclipse!

However, if you’re working on a big Enterprise application, the Maven way is recommended since it’s also important to run Spock-powered unit tests as part of the build process (i.e. Jenkins).

Testing Groovy code with Spock

So let’s assume that you already have a simple class in Groovy called Adder and you want to write a unit test for this class. Here is the Adder.groovy code:

class Adder {

def add(first,second)

{

return first + second

}

}

And here is the unit test:

import spock.lang.*

import com.zeroturnaround.blog.Adder

class AdderTest extends spock.lang.Specification{

def "adder-test"() {

given: "a new Adder class is created"

def adder = new Adder();

expect: "Adding two numbers to return the sum"

adder.add(3, 4) == 7

}

}

This example might seem a bit naive, but you should already notice the compact code for this unit test compared to JUnit. Of course, one major factor is that Groovy itself is more compact than Java. But Spock itself also has some interesting properties:

- The code is written in a behaviour style, which is closer to English than to programming language code

- The class has clear sections annotated by labels (given: and expect:) that clearly identify the purpose of the code statements they contain

- Each label has a comment in the same line that provides a brief description of the business logic

- There are no “assert” methods (like JUnit). The code is much more compact.

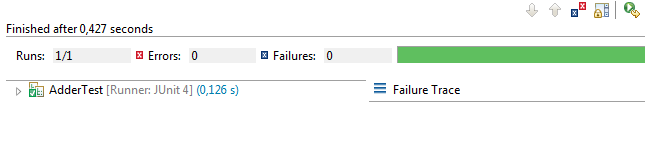

To run this example you just right-click on the AdderTest.groovy file and select “run as JUnit test”! And since Spock is compatible with JUnit runners, you don’t need to change your existing infrastructure.

Ok, so this example wasn’t very exciting. But as I wrote in the introduction, we are more interested in testing Java code with Spock and comparing it with JUnit/Mockito than looking at how it works with Groovy code. So let’s check that out.

Using Spock instead of JUnit for testing Java code

In the previous section, you have seen a bit of the Spock/Groovy syntax. Notice however that Groovy is a language that runs on the JVM and provides excellent compatibility with existing Java code. If you are interested in Groovy itself see the feature post on The Adventurous Developer’s Guide to JVM languages – Groovy.

Therefore we can exploit the Groovy-Java compatibility and use Spock to directly test Java classes. Let’s return back to the weight calculator class of an imaginary e-shop as introduced in my first post about unit testing.

public class BasketWeightCalculator {

private int totalWeight = 0;

public void addItem(int itemWeight) // Assume weight is always an integer

// number

{

totalWeight = totalWeight + itemWeight;

}

public int getTotalWeight() {

return totalWeight;

}

}

We can test this Java class using Spock! And because of the Groovy syntax the unit test is much less verbose. Here is the BasketWeightTest.groovy file:

class BasketWeightTest extends spock.lang.Specification{

def "one-item"() {

given:

def weightCalculator = new BasketWeightCalculator()

when: "add only one item"

weightCalculator.addItem(5)

then: "expect value of the item"

weightCalculator.getTotalWeight() == 5

}

def "two-items"() {

given:

def weightCalculator = new BasketWeightCalculator()

when: "add two items in the basket"

weightCalculator.addItem(5)

weightCalculator.addItem(13)

then: "expect the sum of both items"

weightCalculator.getTotalWeight() == 18

}

def "order-of-items-does-not-matter"() {

given:

def weightCalculator1 = new BasketWeightCalculator()

def weightCalculator2 = new BasketWeightCalculator()

when: "add same items but with different order"

weightCalculator1.addItem(5)

weightCalculator1.addItem(13)

weightCalculator2.addItem(13)

weightCalculator2.addItem(5)

then: "expect both baskets to weigh the same"

weightCalculator1.getTotalWeight() == 18

weightCalculator2.getTotalWeight() == 18

}

Again, nothing really groundbreaking here. This is a direct port from the Java code from the respective blog post.

The expressiveness power of Spock Testing only starts to appear when you start writing more advanced unit tests. In my previous post on Parameterized JUnit tests, we covered an example where a Java class called MyUrlValidator is tested using JUnit parameters.

@RunWith(Parameterized.class)

public class MyUriValidatorTest{

private MyUriValidator myValidator = null;

private String uriTestedNow =null;

private boolean expectedResult = false;

public MyUriValidatorTest(String uriTestedNow,boolean expectedResult)

{

this.uriTestedNow = uriTestedNow;

this.expectedResult = expectedResult;

}

@Parameters

public static Collection<Object[]> data() {

/* First element is the URI, second is the expected result */

List<Object[]>; uriToBeTested = Arrays.asList(new Object[][] {

{ "http://www.google.com", true },

{ "file://home/users", true },

{"http://localhost:8080/", false } });

return uriToBeTested;

}

@Before

public void beforeEachTest() {

myValidator = new MyUriValidator();

myValidator.allowFileUrls(true);

myValidator.allowInternationlizedDomains(false);

myValidator.allowReservedDomains(false);

myValidator.allowCustomPorts(true);

}

@Test

public void testCurrentUri() {

assertEquals("Testing for "+uriTestedNow, expectedResult,myValidator.isValidUrl(uriTestedNow));

}

}

While this code works fine, it is very verbose. Extra annotations, 2-dimensional Object arrays (ouch!), a special constructor and extra class fields are added into the mix.

By comparison, notice how elegant and compact the respective Spock code is below!

class MyUrlValidatorTest extends spock.lang.Specification{

def "test-multiple-urls"() {

given: "create the validator object"

def myValidator = new MyUriValidator()

myValidator.allowFileUrls(true)

myValidator.allowInternationlizedDomains(false)

myValidator.allowReservedDomains(false)

myValidator.allowCustomPorts(false)

expect: "Validate a URL and see if it is valid"

valid == myValidator.isValidUrl(aTestUrl)

where:

aTestUrl | valid

"http://www.google.com" | true

"file://home/users"| true

"http://localhost:8080/" | false

}

}

As with the JUnit unit test, this code is very flexible since adding a new URL is a single line change. But the difference with using Spock, however, is that you get much more readable and efficient code, giving only what is needed by the business logic without all the ugly setup: the JUnit test has 56 lines of code while the Groovy one is only 25!

Using Spock instead of Mockito for mocking Java code

Another very convenient feature of Spock is that it contains its own built-in mocking library.

By default, Spock can only mock Java interfaces. You must add the cglib library as a dependency if you want to mock concrete Java classes like Mockito does. This is easily accomplished using Maven:

<dependency>

<groupId>cglib</groupId>

<artifactId>cglib-nodep</artifactId>

<version>2.2.2</version>

</dependency>

Now you are ready to start mocking!

We have already shown you Mockito in the Alternate Realities blog post. We will now re-write the same unit test using the built-in Mocking mechanism of Spock (which itself has a lot of similarities with Mockito). Here is the FinalInvoiceStepMocked.groovy file:

class FinalInvoiceStepMocked extends spock.lang.Specification{

def "different-customer-types-test"() {

setup:

def printerService = Mock(PrinterService)

def emailService = Mock(EmailService)

def customer = new Customer()

def finalInvoiceStep = new FinalInvoiceStep(printerService, emailService)

def invoice = new Invoice()

when: "customer is normal and has an email inbox"

customer.wantsEmail(true)

finalInvoiceStep.handleInvoice(invoice, customer)

then: "nothing should be printed. Only an email should be sent"

0 * printerService.printInvoice(invoice)

1 * emailService.sendInvoice(invoice,customer.getEmail())

when: "customer is old fashioned and prefers snail mail"

customer.wantsEmail(false)

finalInvoiceStep.handleInvoice(invoice, customer)

then: "no email is available. A copy must have been sent to the printer"

0 * emailService.sendInvoice(invoice,_)

1 * printerService.printInvoice(invoice)

}

}

Again, notice that the labels with English are like descriptions. They create a very natural flow when somebody reads the unit test and tries to understand what it does. The numbers before statements are cardinalities. Zero (0) means that this method should NOT have been called at all. One (1) means that this method should be called only once. The _ (underscore) character is a matcher and means “any argument”.

For more information on Mocking with Spock (including how to setup mock answers, more argument matchers, method matchers and spy objects) see the official documentation.

Conclusion

In this post we discovered that Spock, which is a testing framework for Groovy, can also be used for Java code and brings about a combined benefit of both testing and mocking abilities in a single package. I see this as providing a complete solution for your unit and integration tests.

Although Spock has not reached the 1.0 release yet, it offers several advanced features for testing that make it a viable alternative to JUnit mockito. Keep an eye on Spock, because as it matures, the compact code of Groovy tests compared to verbose JUnit/TestNG code might entice you to write your whole unit test in Groovy DSL. But we’ll keep our fingers crossed for that.

Go back to contents, contact me via email or find me at Twitter if you have a comment.