Software Testing Anti-patterns

21 Apr 2018Introduction

There are several articles out there that talk about testing anti-patterns in the software development process. Most of them however deal with the low level details of the programming code, and almost always they focus on a specific technology or programming language.

In this article I wanted to take a step back and catalog some high-level testing anti-patterns that are technology agnostic. Hopefully you will recognize some of these patterns regardless of your favorite programming language.

Terminology

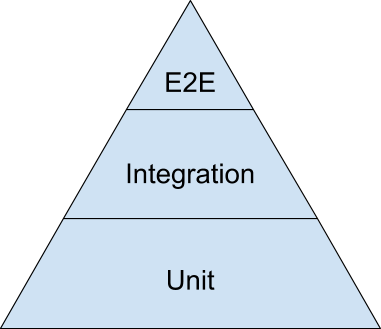

Unfortunately, testing terminology has not reached a common consensus yet. If you ask 100 developers what is the difference between an integration test, a component test and an end-to-end test you might get 100 different answers. For the purposes of this article I will focus on the definition of the test pyramid as presented below.

If you have never encountered the testing pyramid before, I would urge you to become familiar with it first before going on. Some good starting points are:

- The forgotten layer of the test automation pyramid (Mike Cohn 2009)

- The Test Pyramid (Martin Fowler 2012)

- Google Testing blog (Google 2015)

- The Practical Test Pyramid (Ham Vocke 2018)

The testing pyramid deserves a whole discussion on its own, especially on the topic of the amount of tests needed for each category. For the current article I am just referencing the pyramid in order to define the two lowest test categories. Notice that in this article User Interface Tests (the top part of the pyramid) are not mentioned (mainly for brevity reasons and because UI tests come with their own specific anti-patterns).

Therefore the two major test categories mentioned as unit and integration tests from now on are:

| Tests | Focus on | Require | Speed | Complexity | Setup needed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit tests | a class/method | the source code | very fast | low | No |

| Integration tests | a component/service | part of the running system | slow | medium | Yes |

Unit tests are the category of tests that have wider acceptance regarding the naming and what they mean. They are the tests that accompany the source code and have direct access to it. Usually they are executed with an xUnit framework or similar library. These tests work directly on the source code and have full view of everything. A single class/method/function is tested (or whatever is the smallest possible working unit for that particular business feature) and anything else is mocked/stubbed.

Integration tests (also called service tests, or even component tests) focus on a whole component. A component can be a set of classes/methods/functions, a module, a subsystem or even the application itself. They examine the component by passing input data and examinining the output data it produces. Usually some kind of deployment/bootstrap/setup is required first. External systems can be mocked completely, replaced (e.g. using an in-memory database instead of a real one), or the real external dependency might be used depending on the business case. Compared to unit tests they may require more specialized tools either for preparing the test environment, or for interacting/verifying it.

The second category suffers from a blurry definition and most naming controversies regarding testing start here. The “scope” for integration tests is also highly controversial and especially the nature of access to the application (black or white box testing and whether mocking is allowed or not).

As a basic rule of thumb if

- a test uses a database

- a test uses the network to call another component/application

- a test uses an external system (e.g. a queue or a mail server)

- a test reads/writes files or performs other I/O

- a test does not rely on the source code but instead it uses the deployed binary of the app

…then it is an integration test and not a unit test.

With the naming out of the way, we can dive into the list. The order of anti-patterns roughly follows their appearance in the wild. Frequent problems are gathered in the top positions.

Software Testing Anti-Pattern List

- Having unit tests without integration tests

- Having integration tests without unit tests

- Having the wrong kind of tests

- Testing the wrong functionality

- Testing internal implementation

- Paying excessive attention to test coverage

- Having flaky or slow tests

- Running tests manually

- Treating test code as a second class citizen

- Not converting production bugs to tests

- Treating TDD as a religion

- Writing tests without reading documentation first

- Giving testing a bad reputation out of ignorance

Anti-Pattern 1 - Having unit tests without integration tests

This problem is a classic one with small to medium companies. The application that is being developed in the company has only unit tests (the base of the pyramid) and nothing else. Usually lack of integration tests is caused by any of the following issues:

- The company has no senior developers. The team has only junior developers fresh out of college who have only seen unit tests

- Integration tests existed at one point but were abandoned because they caused more trouble than their worth. Unit tests were much more easy to maintain and so they prevailed.

- The running environment of the application is very “challenging” to setup. Features are “tested” in production.

I cannot really say anything about the first issue. Every effective team should have at least some kind of mentor/champion that can show good practices to the other members. The second issue is covered in detail in anti-patterns 5, 7 and 8.

This brings us to the last issue - difficulty in setting up a test environment. Now don’t get me wrong, there are indeed some applications that are really hard to test. Once I had to work with a set of REST applications that actually required special hardware on their host machine. This hardware existed only in production, making integration tests very challenging. But this is a corner case.

For the run-of-the-mill web or back-end application that the typical company creates, setting up a test environment should be a non-issue. With the appearance of Virtual Machines and lately Containers this is more true than ever. Basically if you are trying to test an application that is hard to setup, you need to fix the setup process first before dealing with the tests themselves.

But why are integration tests essential in the first place?

The truth here is that there are some types of issues that only integration tests can detect. The canonical example is everything that has to do with database operations. Database transactions, database triggers and any stored procedures can only be examined with integration tests that touch them. Any connections to other modules either developed by you or external teams need integration tests (a.k.a. contract tests). Any tests that need to verify performance, are integration tests by definition. Here is a summary on why we need integration tests:

| Type of issue | Detected by Unit tests | Detected by Integration tests |

|---|---|---|

| Basic business logic | yes | yes |

| Component integration problems | no | yes |

| Transactions | no | yes |

| Database triggers/procedures | no | yes |

| Wrong Contracts with other modules/APIs | no | yes |

| Wrong Contracts with other systems | no | yes |

| Performance/Timeouts | no | yes |

| Deadlocks/Livelocks | maybe | yes |

| Cross-cutting Security Concerns | no | yes |

Basically any cross-cutting concern of your application will require integration tests. With the recent microservice craze integration tests become even more important as you now have contracts between your own services. If those services are developed by other teams, you need an automatic way to verify that interface contracts are not broken. This can only be covered with integration tests.

To sum up, unless you are creating something extremely isolated (e.g. a command line linux utility), you really need integration tests to catch issues not caught by unit tests.

Anti-Pattern 2 - Having integration tests without unit tests

This is the inverse of the previous anti-pattern. This anti-pattern is more common in large companies and large enterprise projects. Almost always the history behind this anti-pattern involves developers who believe that unit tests have no real value and only integration tests can catch regressions. There is a large majority of experienced developers who consider unit tests a waste of time. Usually if you probe them with questions, you will discover that at some point in the past, upper management had forced them to increase code coverage (See anti-pattern 6) forcing them to write trivial unit tests.

It is true that in theory you could have only integration tests in a software project. But in practice this would become very expensive to test (both in developer time and in build time). We saw in the table of the previous section that integration tests can also find business logic errors after each run, and so they could “replace” unit tests in that manner. But is this strategy viable in the long run?

Integration tests are complex

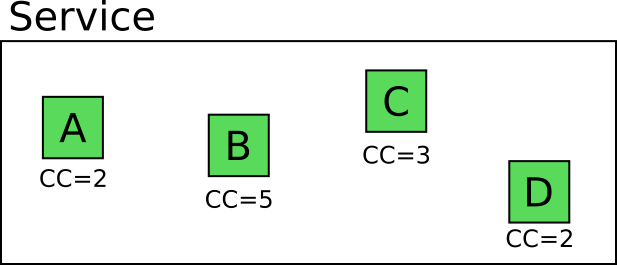

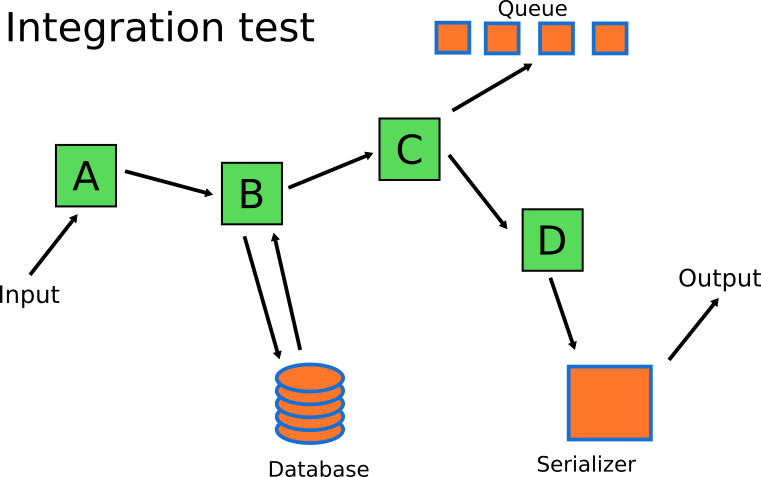

Let’s look at an example. Assume that you have a service with the following 4 methods/classes/functions.

The number on each module denotes its cyclomatic complexity or in other words the separate code paths this module can take.

Mary “by the book” Developer wants to write unit tests for this service (because she understands that unit tests do have value). How many tests does she need to write in order to get full coverage of all possible scenarios?

It should be obvious that one can write 2 + 5 + 3 + 2 = 12 isolated unit tests that cover fully the business logic of these modules. Remember that this number is just for a single service, and the application Mary is working on, has multiple services.

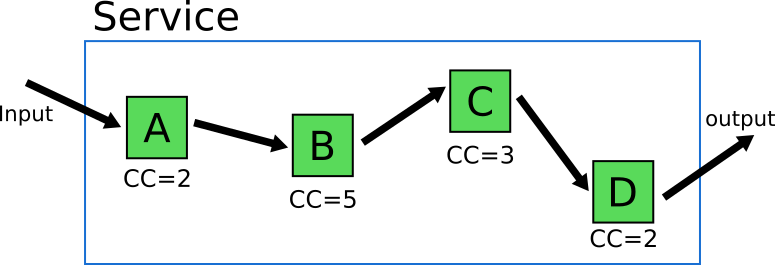

Joe “Grumpy” developer on the other hand does not believe in the value of unit tests. He thinks that unit tests are a waste of time and he decides to write only integration tests for this module. How many integration tests should he write? He starts looking at all the possible paths a request can take in that service.

Again it should be obvious that all possible scenarios of codepaths are 2 * 5 * 3 * 2 = 60. Does that mean that Joe will actually write 60 integration tests? Of course not! He will try and cheat. He will try to select a subset of integration tests that feel “representative”. This “representative” subset of tests will give him enough coverage with the minimum amount of effort.

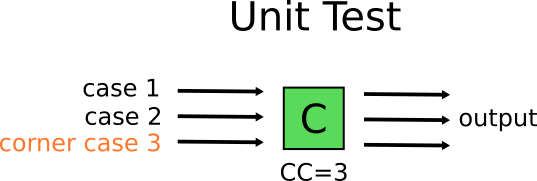

This sounds easy enough in theory, but can quickly become problematic. The reality is that these 60 code paths are not created equally. Some of them are corner cases. For example if we look at module C we see that is has 3 different code paths. One of them is a very special case, that can only be recreated if C gets a special input from component B, which is itself a corner case and can only be obtained by a special input from component A. This means that this particular scenario might require a very complex setup in order to select the inputs that will trigger the special condition on the component C.

Mary on the other hand, can just recreate the corner case with a simple unit test, with no added complexity at all.

Does that mean that Mary will only write unit tests for this service? After all that will lead her to anti-pattern 1. To avoid this, she will write both unit and integration tests. She will keep all unit tests for the actual business logic and then she will write 1 or 2 integration tests that make sure that the rest of the system works as expected (i.e. the parts that help these modules do their job)

The integration tests needed in this system should focus on the rest of the components. The business logic itself can be handled by the unit tests. Mary’s integration tests will focus on testing serialization/deserialization and with the communication to the queue and the database of the system.

In the end, the number of integration tests will be much smaller than the number of unit tests (matching the shape of the test pyramid described in the first section of this article).

Integration tests are slow

The second big issue with integration tests apart from their complexity is their speed. Usually an integration test is one order of magnitute slower than a unit test. Unit tests need just the source code of the application and nothing else. They are almost always CPU bound. Integration tests on the other hand can perform I/O with external systems making them much more difficult to run in an effective manner.

Just to get an idea on the difference for the running time let’s assume the following numbers.

- Each unit test takes 60ms (on average)

- Each integration test takes 800ms (on average)

- The application has 40 services like the one shown in the previous section

- Mary is writing 10 unit tests and 2 integration tests for each service

- Joe is writing 12 integration tests for each service

Now let’s do the calculations. Notice that I assume that Joe has found the perfect subset of integration tests that give him the same code coverage as Mary (which would not be true in a real application).

| Time to run | Having only integration tests (Joe) | Having both Unit and Integration tests (Mary) |

|---|---|---|

| Just Unit tests | N/A | 24 seconds |

| Just Integration tests | 6.4 minutes | 64 seconds |

| All tests | 6.4 minutes | 1.4 minutes |

The difference in total running time is enormous. Waiting for 1 minute after each code change is vastly different than waiting for 6 minutes. The 800ms I assumed for each integration test is vastly conservative. I have seen integration test suites where a single test can take several minutes on its own.

In summary, trying to use only integration tests to cover business logic is a huge time sink. Even if you automate the tests with CI, your feedback loop (time from commit to getting back the test result) will be very long.

Integration tests are harder to debug than unit tests

The last reason why having only integration tests (without any unit tests) is an anti-pattern is the amount of time spent to debug a failed test. Since an integration test is testing multiple software components (by definition), when it breaks, the failure can come from any of the tested components. Pinpointing the problem can be a hard task depending on the number of components involved.

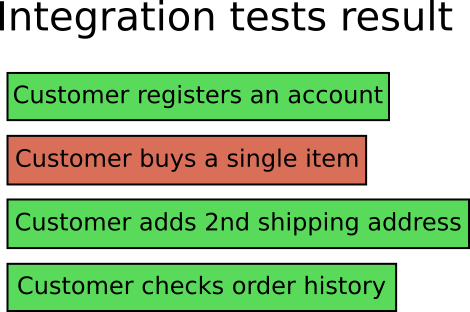

When an integration tests fails you need to be able to understand why it failed and how to fix it. The complexity and breadth of integration tests make them extremely difficult to debug. Again, as an example let’s say that your application only has integration tests. The application you are developing is the typical e-shop.

A developer in your team (or even you) creates a new commit, which triggers the integration tests with the following result:

As a developer you look at the test result and see that the integration test named “Customer buys item” is broken. In the context of an e-shop application this is not very helpful. There are many reasons why this test might be broken.

There is no way to know why the test broke without diving into the logs and metrics of the test environment (assuming that they can pinpoint the problem). In several cases (and more complex applications) the only way to truly debug an integration test is to checkout the code, recreate the test environment locally, then run the integration tests and see it fail in the local development environment.

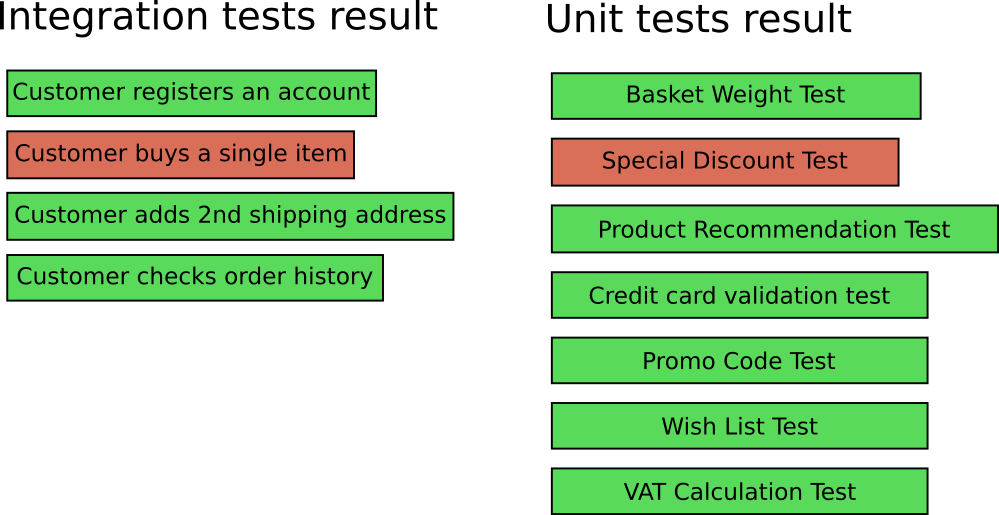

Now imagine that you work with Mary on this application so you have both integration and unit tests. Your team makes some commits, you run all the tests and get the following:

Now two tests are broken:

- “Customer buys item” is broken as before (integration test)

- “Special discount test” is also broken (unit test)

It is now very easy to see the where to start looking for the problem. You can go directly to the source code of the Discount functionality, locate the bug and fix it and in 99% of the cases the integration test will be fixed as well.

Having unit tests break before or with integration tests is a much more painless process when you need to locate a bug.

Quick summary of why you need unit tests

This is the longest section of this article, but I consider it very important. In summary while in theory you could only have integration tests, in practice

- Unit tests are easier to maintain

- Unit tests can easily replicate corner cases and not-so-frequent scenarios

- Unit tests run much faster than integration tests

- Broken unit tests are easier to fix than broken integration tests

If you only have integration tests, you waste developer time and company money. You need both unit and integration tests are the same time. They are not mutually exclusive. There are several articles on the internet that advocate using only one type of tests. All these articles are misinformed. Sad but true.

Anti-Pattern 3 - Having the wrong kind of tests

Now that we have seen why we need both kinds of tests (unit and integration), we need to decide on how many tests we need from each category.

There is no hard and fast rule here, it depends on your application. The important point is that you need to spend some time to understand what type of tests add the most value to your application. The test pyramid is only a suggestion on the amount of tests that you should create. It assumes that you are writing a commercial web application, but that is not always the case. Let’s see some examples:

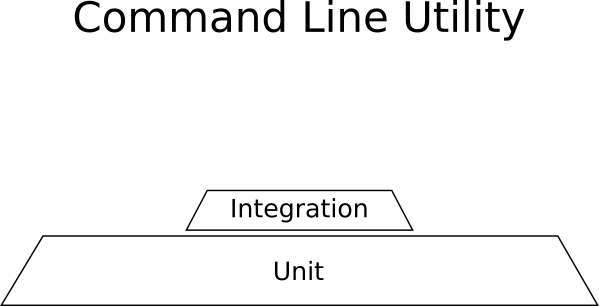

Example - Linux command line utility

Your application is a command line utility. It reads one special format of a file (let’s say a CSV) and exports another format (let’s say JSON) after doing some transformations. The application is self-contained, does not communicate with any other system or use the network. The transformations are complex mathematical processes that are critical for the correct functionality of the application (it should always be correct even if it slow).

In this contrived example you would need:

- Lots and lots of unit tests for the mathematical equations.

- Some integration tests for the CSV reading and JSON writing

- No GUI tests because there is no GUI.

Here is the breakdown of tests for this project:

Unit tests dominate in this example and the shape is not a pyramid.

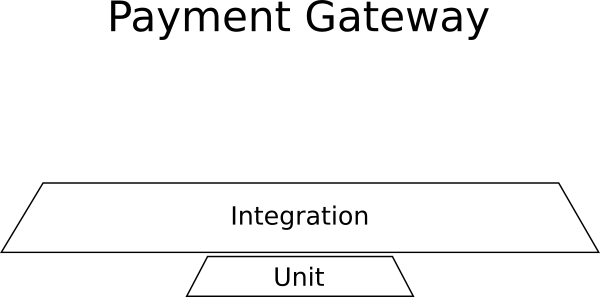

Example - Payment Management

You are adding a new application that will be inserted into an existing big collection of enterprise systems. The application is a payment gateway that processes payment information for an external system. This new application should keep a log of all transactions to an external DB, it should communicate with external payment providers (e.g. Paypal, Stripe, WorldPay) and it should also send payment details to another system that prepares invoices.

In this contrived example you would need

- Almost no unit tests because there is no business logic

- Lots and lots of integration tests for the external communications, the db storage, the invoice system

- No UI Tests because there is a no UI

Here is the breakdown of tests for this project:

Integrations tests dominate in this example and the shape is not a pyramid.

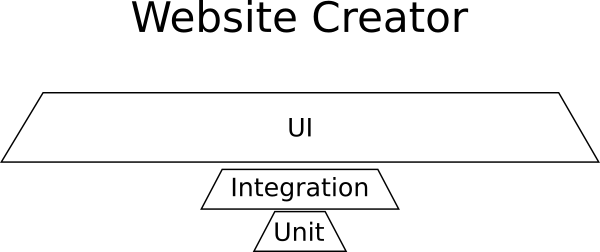

Example - Website creator

You are working on this brand new startup that will revolutionize the way people create websites, by offering a one-of-a-kind way to create web applications from within the browser.

The application is a graphical designer with a toolbox of all the possible HTML elements that can be added on a web page along with library of premade templates. There is also the ability to get new templates from a marketplace. The website creator works in a very friendly way by allowing you to drag and drop components on the page, resize them, edit their properties and change their colors and appearance.

In this contrived example you would need

- Almost no unit tests because there is no business logic

- Some integration tests for the marketplace

- Lots and lots of UI tests that make sure the user experience is as advertised

Here is the breakdown of tests for this project:

UI tests dominate here and the shape is not a pyramid.

I used some extreme examples to illustrate the point that you need to understand what your application needs and focus only on the tests that give you value. I have personally seen “payment management” applications with no integration tests and “website creator” applications with no UI tests.

There are several articles on the web (I am not going to link them) that talk about a specific amount on integration/unit/UI tests that you need or don’t need. All these articles are based on assumptions that may not be true in your case.

Anti-Pattern 4 - Testing the wrong functionality

In the previous sections we have outlined the types and amount of tests you need to have for your application. The next logical step is to explain what functionality you actually need to test.

In theory, getting 100% code coverage in an application is the ultimate goal. In practice this goal is not only difficult to achieve but also it doesn’t guarantee a bug free application.

There are some cases where indeed it is possible to test all functionality of your application. If you start on a green-field project, if you work in a small team that is well behaved and takes into account the effort required for tests, it is perfectly fine to write new tests for all new functionality you add (because the existing code already has tests).

But not all developers are lucky like this. In most cases you inherit an existing application that has a minimal amount of tests (or even none!). If you are part of a big and established company, working with legacy code is mostly the rule rather than the exception.

Ideally you would have enough development time to write tests for both new and existing code for a legacy application. This is a romantic idea that will probably be rejected by the average project manager who is mostly interested on adding new features rather then testing/refactoring. You have to pick your battles and find a fine balance between adding new functionality (as requested by the business) and expanding the existing test suite.

So what do you test? Where do you focus your efforts? Several times I have seen developers wasting valuable testing time by writing “unit tests” that add little or no value to the overall stability of the application. The canonical example of useless testing is trivial tests that verify the application data model.

Code coverage is analyzed in detail in its own anti-pattern section. In the present section however we will talk about code “severity” and how it relates to your tests.

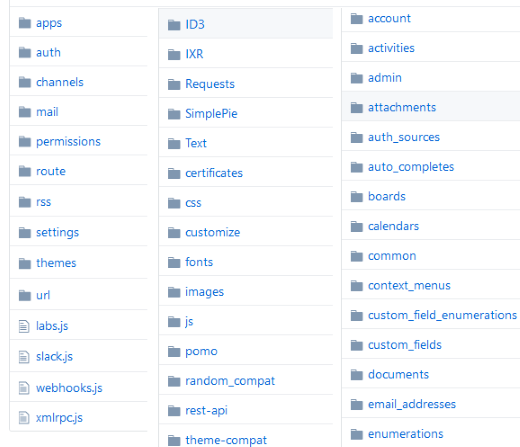

If you ask any developer to show you the source code of any application, he/she will probably open an IDE or code repository browser and show you the individual folders.

This representation is the physical model of the code. It defines the folders in the filesystem that contain the source code. While this hierarchy of folders is great for working with the code itself, unfortunately it doesn’t define the importance of each code folder. A flat list of code folders implies that all code components contained in them are of equal importance.

This is not true as different code components have a different impact in the overall functionality of the application. As a quick example let’s say that you are writing an eshop application and two bugs appear in production:

- Customers cannot check-out their cart halting all sales

- Customers get wrong recommendations when they browse products.

Even though both bugs should be fixed, it is obvious that the first one has higher priority. Therefore if you inherit an eshop application with zero tests, you should write new tests the directly validate the check-out functionality rather than the recommendation engine. Despite the fact that the recommendation engine and the check-out process might exist on sibling folders in the filesystem, their importance is different when it comes to testing.

To generalize this example, if you work for some time in any medium/large application you will soon need to think about code using a different representation - the mental model.

I am showing here 3 layers of code, but depending on the size of your application it might have more. These are:

- Critical code - This is the code that breaks often, gets most of new features and has a big impact on application users

- Core code - This is the code that breaks sometimes, gets few new features and has medium impact on the application users

- Other code - This is code that rarely changes, rarely gets new features and has minimal impact on application users.

This mental mode should be your guiding principle whenever you write a new software test. Ask yourself if the functionality you are writing tests for now belongs to the critical or core categories. If yes, then write a software test. If no, then maybe your development time should better be spent elsewhere (e.g. in another bug).

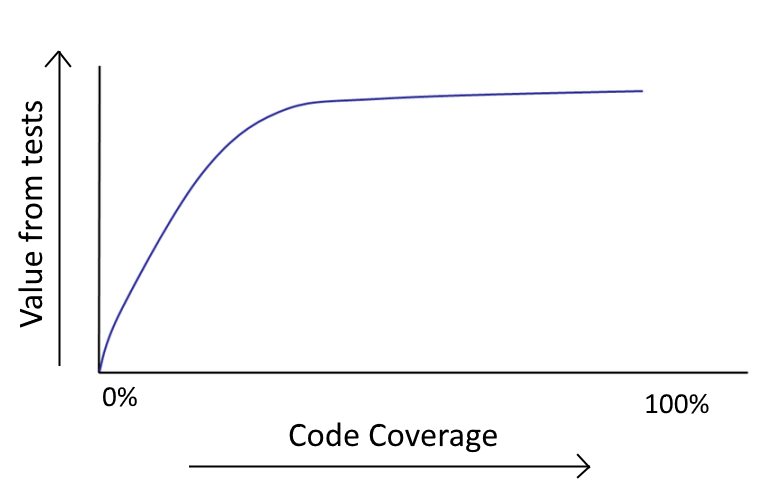

The concept of having code with different severity categories is also great when you need to answer the age old question of how much code coverage is enough for an application. To answer this question you need to either know the severity layers of the application or ask somebody that does. Once you have this information at hand the answer is obvious:

Try to write tests that work towards 100% coverage of critical code. If you have already done this, then try to write tests that work towards 100% of core code. Trying however to get 100% coverage on total code is not recommended.

The important thing to notice here is that the critical code in an application is always a small subset of the overall code. So if in an application critical code is let’s say 20% of the overall code, then getting just 20% overall code coverage is a good first step for reducing bugs in production.

In summary, write unit and integration tests for code that

- breaks often

- changes often

- is critical to the business

If you have the time luxury to further expand the test suite, make sure that you understand the diminishing returns before wasting time on tests with little or no value.

Anti-Pattern 5 - Testing internal implementation

More tests are always a good thing. Right?

Wrong! You also need to make sure that the tests are actually structured in a correct way. Having tests that are written in the wrong manner is bad in two ways.

- They waste precious development time the first time they are written

- They waste even more time when they need to be refactored (when a new feature is added)

Strictly speaking, test code is like any other type of code. You will need to refactor it at some point in order to improve it in a gradual way. But if you find yourself routinely changing existing tests just to make them pass when a new feature is added then your tests are not testing what they should be testing.

I have seen several companies that started new projects and thinking that they will get it right this time, they started writing a big number of tests to cover the functionality of the application. After a while, a new feature got added and several existing tests needed to change in order to make them pass again. Then another new feature was added and more tests needed to be updated. Soon the amount of effort spent refactoring/fixing the existing tests was actually larger than the time needed to implement the feature itself.

In such situations, several developers just accept defeat. They declare software tests a waste of time and abandon completely the existing test suite in order to focus fully on new features. In some extreme scenarios some changes might even be held back because of the amount of tests that break.

The problem here is of course the bad quality of tests. Tests that need to be refactored all the time suffer from tight coupling with the main code. Unfortunately, you need some basic testing experience to understand which tests are written in this “wrong” way.

Having to change a big number of existing tests when a new feature is introduced shows the symptom. The actual problem is that tests were instructed to verify internal implementation which is always a recipe for disaster. There are several software testing resources online that attempt to explain this concept, but very few of them show some solid examples.

I promised in the beginning of this article that I will not speak about a particular programming language and I intend to keep that promise. In this section the illustrations show the data structure of your favorite programming language. Think of them as structs/objects/classes that contain fields/values.

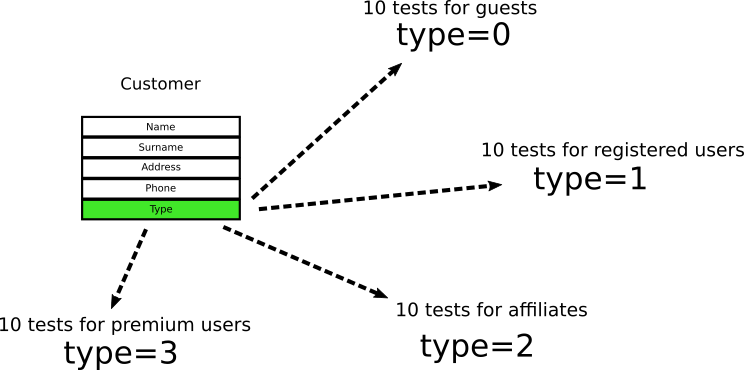

Let’s say that the customer object in an e-shop application is the following:

The customer type has only two values where 0 means “guest user” and 1 means “registered user”. Developers look at the object and write 10 unit tests that verify various cases of guests users and 10 cases of registered user. And when I say “verify” I mean that tests are looking at this particular field in this particular object.

Time passes by and business decides that a new customer type with value 2 is needed for affiliates. Developers add 10 more tests that deal with affiliates. Finally another type of user called “premium customer”

is added and developers add 10 more tests.

At this point, we have 40 tests in 4 categories that all look at this particular field. (These numbers are imaginary. This contrived example exists only for demonstration purposes. In a real project you might have 10 interconnected fields within 6 nested objects and 200 tests).

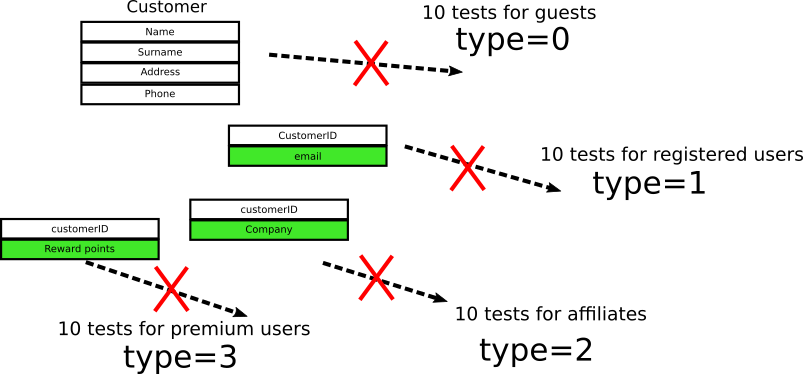

If you are a seasoned developer you can always imagine what happens next. New requirements come that say:

- For registered users, their email should also be stored

- For affiliate users, their company should also be stored

- Premium users can now gather reward points.

The customer object now changes as below:

You now have 4 objects connected with foreign keys and all 40 tests are instantly broken because the field they were checking no longer exists.

Of course in this trivial example one could simply keep the existing field to not break backwards compatibility with tests. In a real application this is not always possible. Sometimes backwards compatibility might essentially mean that you need to keep both old and new code (before/after the new feature) resulting in a huge bloat. Also notice that having to keep old code around just to make unit tests pass is a huge anti-pattern on its own.

In a real application when this happens, developers ask from management some extra time to fix the tests. Project managers then declare that unit testing is a waste of time because they seem to hinder new features. The whole team then abandons the test suite by quickly disabling the failing tests.

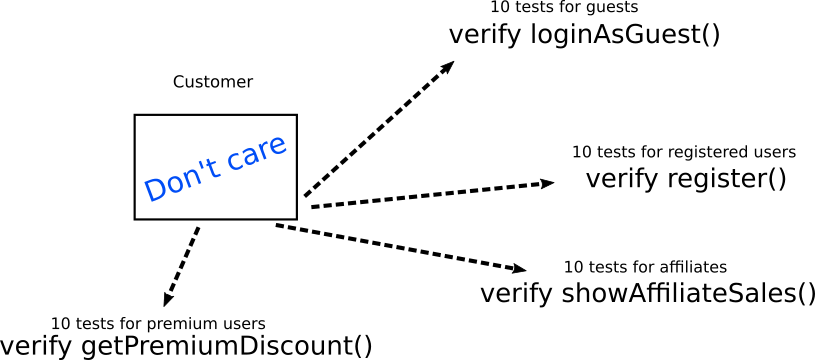

The big problem here is not testing, but instead the way the tests were constructed. Instead of testing internal implementation they should instead expected behavior. In our simple example instead of testing directly the internal structure of the customer they should instead check the exact business requirement of each case. Here is how these same tests should be handled instead.

The tests do not really care about the internal structure of the customer object. They only care about its interactions with other objects/methods/functions. The other objects/method/functions should be mocked when needed on a case to case basis. Notice that each type of tests directly maps to a business need rather than a technical implementation (which is always a good practice.)

If the internal implementation of the Customer object changes, the verification code of the tests remains the same. The only thing that might change is the setup code for each test, which should be centralized in a single helper function called createSampleCustomer() or something similar (more on this in AntiPattern 9)

Of course in theory it is possible for the verified objects themselves to change. In practice it is not realistic for changes to happen at loginAsGuest() and register() and showAffiliateSales() and getPremiumDiscount() at the same time. In a realistic scenario you would have to refactor 10 tests instead of 40.

In summary, if you find yourself continuously fixing existing tests as you add new features, it means that your tests are tightly coupled to internal implementation.

Anti-Pattern 6 - Paying excessive attention to test coverage

Code coverage is a favorite metric among software stakeholders. Endless discussions have happened (and will continue to happen) among developers and project managers on the amount of code coverage a project needs.

The reason why everybody likes to talk about code coverage is because it is a metric that is easy to understand and quantify. There are several easily accessible tools that output this metric for most programming languages and test frameworks.

Let me tell you a little secret: Code coverage is completely useless as a metric. There is no “correct” code coverage number. This is a trap question. You can have a project with 100% code coverage that still has bugs and problems. The real metrics that you should monitor are the well-known CTM.

The Codepipes Testing Metrics (CTM)

Here is their definition if you have never seen them before:

| Metric Name | Description | Ideal value | Usual value | Problematic value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDWT | % of Developers writing tests | 100% | 20%-70% | Anything less than 100% |

| PBCNT | % of bugs that create new tests | 100% | 0%-5% | Anything less than 100% |

| PTVB | % of tests that verify behavior | 100% | 10% | Anything less than 100% |

| PTD | % of tests that are deterministic | 100% | 50%-80% | Anything less than 100% |

PDWT (Percent of Developers who Write Tests) is probably the most important metric of all. There is no point in talking about software testing anti-patterns if you have zero tests in the first place. All developers in the team should write tests. A new feature should be declared done only when it is accompanied by one or more tests.

PBCNT (Percent of Bugs that Create New tests). Every bug that slips into production is a great excuse for writing a new software test that verifies the respective fix. A bug that appears in production should only appear once. If your project suffers from bugs that appear multiple times in production even after their original “fix”, then your team will really benefit from this metric. More details on this topic in Antipattern 10.

PTVB (Percent of Tests that Verify Behavior and not implementation). Tightly coupled tests are a huge time sink when the main code is refactored. This topic was already discussed in Antipattern 5.

PTD (Percent of Tests that are Deterministic to total tests). Tests should only fail when something is wrong with the business code. Having tests that fail intermittently for no apparent reason is a huge problem that is discussed in Antipattern 7.

If after reading about these metrics, you still insist on setting a hard number as a goal for code coverage, I will give you the number 20%. This number should be used as a rule of thumb and it is based on the Pareto principle. 20% of your code is causing 80% of your bugs, so if you really want to start writing tests you could do well by starting with that code first. This advice also ties well with Anti-pattern 4 where I suggest that you should write tests for your critical code first.

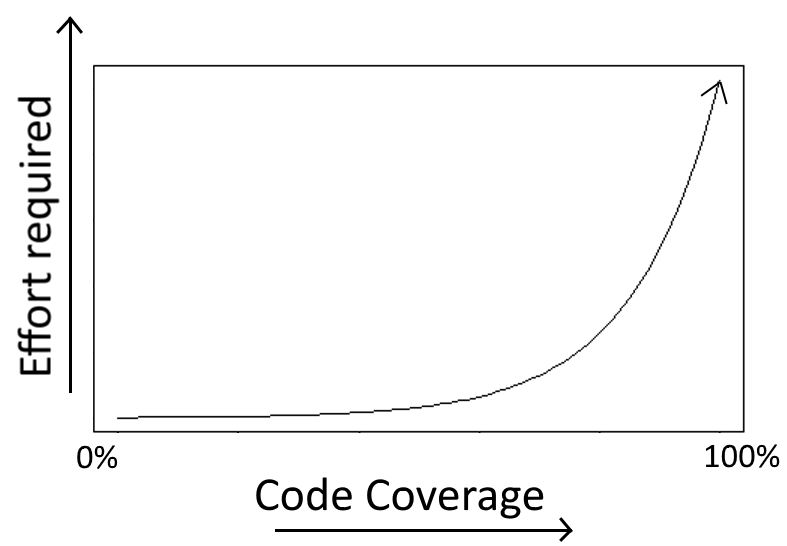

Do not try to achieve 100% total code coverage. Achieving 100% code coverage sounds good in theory but almost always is a waste of time:

- you have wasted a lost of effort as getting from 80% to 100% is much more difficult than getting from 0% to 20%

- Increasing code coverage has diminishing returns

In any non trivial application there are certain scenarios that needs complex unit tests in order to trigger. The effort required to write these tests will usually be more than the risk involved if these particular scenarios ever fail in production (if ever).

If you have worked with any big application you should know by now that after reaching 70% or 80% code coverage, it is getting very hard to write useful tests for the code that is still untested.

On a similar note, as we already saw in the section for Antipattern 4, there are some code paths that never actually fail in production, and therefore writing tests for them is not recommended. The time spent on getting them covered should be better spent on actual features.

Projects that need a specific code coverage percentage as a delivery requirement usually force developers to test trivial code in order or write tests that just verify the underlying programming language. This is a huge waste of time and as a developer you have the duty to complain to management who has such unreasonable demands.

In summary, code coverage is a metric that should not be used as a representation for quality of a software project.

Anti-Pattern 7 - Having flaky or slow tests

This particular anti-pattern has already been documented heavily so I am just including it here for completeness.

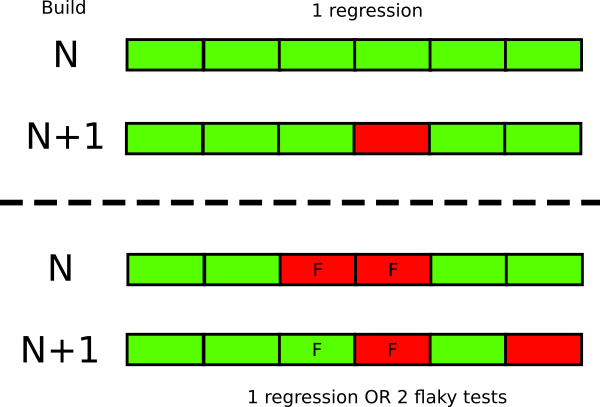

Since software tests act as an early warning against regressions, they should always work in a reliable way. A failing test should be a cause of concern and the person(s) that triggered the respective build should investigate why the test failed right away.

This approach can only work with tests that fail in a deterministic manner. A test that sometimes fails and sometimes passes (without any code changes in between) is unreliable and undermines the whole testing suite. The negative effects are two fold

- Developers do not trust tests anymore and soon ignore them

- Even when non-flaky tests actually fail, it is hard to detect them in a sea of flaky tests

A failing test should be easily recognizable by everybody in your team as it changes the status of the whole build. On the other hand if you have flaky tests it is hard to understand if new failures are truly new or they stem from the existing flaky tests.

Even a small number of flaky tests in enough to destroy the credibility of the rest of test suite. If you have 5 flaky tests for example, run the build and get 3 failures it is not immediately evident if everything is fine (because the failures were coming from the flaky tests) or if you just introduced 3 regressions.

A similar problem is having tests that are really really slow. Developers need a quick feedback on the result of each commit (also discussed in the next section) so slow tests will eventually be ignored or even not run at all.

In practice flaky and slow tests are almost always integration tests and/or UI tests. As we go up in the testing pyramid, the probabilities of flaky tests are greatly increasing. Tests that deal with browser events are notoriously hard to get right all the time. Flakiness in integration tests can come from many factors but the usual suspect is the test environment and its requirements.

The primary defense against flaky and slow tests is to isolate them in their own test suite (assuming that they are not fixable). You can easily find more abundant resources on how to fix flaky tests for your favorite programming language by searching online so there is no point in me explaining the fixes here.

In summary, you should have a reliable test suite (even if it is a subset of the whole test suite) that is rock solid. A test that fails in this suite means that something is really really wrong with the code and any failure means that the code must not be promoted to production.

Anti-Pattern 8 - Running tests manually

Depending on your organization you might actually have several types of tests in place. Unit tests, Load tests, User acceptance tests are common categories of test suites that might be executed before the code goes into production.

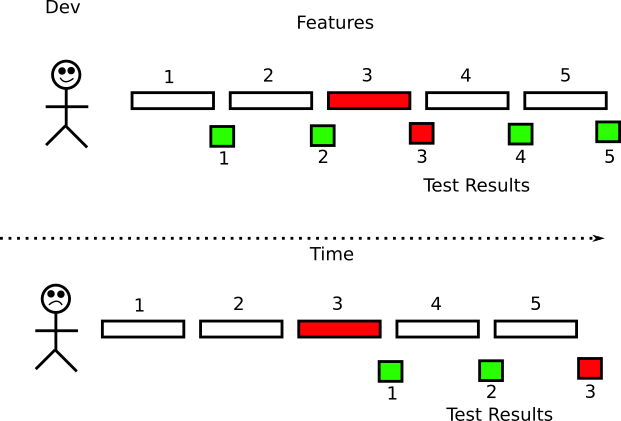

Ideally all your tests should run automatically without any human intervention. If that is not possible at the very least all tests that deal with correctness of code (i.e. unit and integration tests) must run in an automatic manner. This way developers get feedback on the code in the most timely manner. It is very easy to fix a feature when the code is fresh in your mind and you haven’t switched context yet to an unrelated feature.

In the past the most lengthy step of the software lifecycle was the deployment of the application. With the move into cloud infrastructure where machines can be created on demand (either in the form of VMs or containers) the time to provision a new machine has been reduced to minutes or seconds. This paradigm shift has caught a lot of companies by surprise as they were not ready to handle daily or even hourly deployments. Most of the existing practices were centered around lengthy release cycles. Waiting for a specific time in the release to “pass QA” with manual approval is one of those obsolete practices that is no longer applicable if a company wants to deploy as fast as possible.

Deploying as fast as possible implies that you trust each deployment. Trusting an automatic deployment requires a high degree of confidence in the code that gets deployed. While there are several ways of getting this confidence, the first line of defense should be your software tests. However, having a test suite that can catch regressions quickly is only half part of the equation. The other half is running the tests automatically (possibly after every commit).

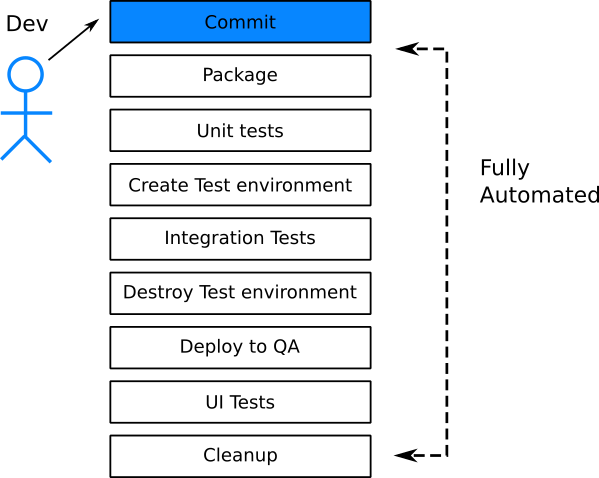

A lot of companies think that they practice continuous delivery and/or deployment. In reality they don’t. Practicing true CI/CD means that at any given point in time there is a version of the code that is ready to be deployed. This means that the candidate release for deployment is already tested. Therefore having a package version of an application “ready” which has not really “passed QA” is not true CI/CD.

Unfortunately, while most companies have correctly realized that deployments should be automated, because using humans for them is error prone and slow, I still see companies where launching the tests is a semi-manual process. And when I say semi-manual I mean that even though the test suite itself might be automated, there are human tasks for house-keeping such as preparing the test environment or cleaning up the test data after the tests have finished. That is an anti-pattern because it is not true automation. All aspects of testing should be automated.

Having access to VMs or containers means that it is very easy to create various test environments on demand. Creating a test environment on the fly for an individual pull request should be a standard practice within your organization. This means that each new feature is tested individually on its own. A problematic feature (i.e. that causes tests to fail) should not block the release of the rest of the features that need to be deployed at the same time.

An easy way to understand the level of test automation within a company is to watch the QA/Test people in their daily job. In the ideal case, testers are just creating new tests that are added to an existing test suite. Testers themselves do not run tests manually. The test suite is run by the build server.

In summary, testing should be something that happens all the time behind the scenes by the build server. Developers should learn the result of the test for their individual feature after 5-15 minutes of committing code. Testers should create new tests and refactor existing ones, instead of actually running tests.

Anti-Pattern 9 - Treating test code as a second class citizen

If you are a seasoned developer, you will spend always some time to structure new code in your mind before implementing it. There are several philosophies regarding code design and some of them are so significant that have their own Wikipedia entry. Some examples are:

The first one is arguably the most important one as it forces you to have a single source of truth for code that is reused across multiple features. Depending on your own programming language you may also have access to several other best practices and recommended design patterns. You might even have special guidelines that are specific to your team.

Yet, for some unknown reason several developers do not apply the same principles to the code that holds the software tests. I have seen projects which have well designed feature code, but suffer from tests with huge code duplication, hardcoded variables, copy-paste segments and several other inefficiencies that would be considered inexcusable if found on the main code.

Treating test code as a second class citizen makes no sense, because in the long run all code needs maintenance. Tests will need to be updated and refactored in the future. Their variables and structure will need to change. If you write tests without thinking about their design you are creating additional technical debt that will be added to the one already present in the main code.

Try to design your tests with the same attention that you give to the feature code. All common refactoring techniques should be used on tests as well. As a starting point

- All test creation code should be centralized. All tests should create test data in the same manner

- Complex verification segments should be extracted in a common domain specific library

- Mocks and stubs that are used too many times should not be copied-pasted.

- Test initialization code should be shared between similar tests.

If you employ tools for static analysis, source formatting or code quality then configure them to run on test code, too.

In summary, design your tests with the same detail that you design the main feature code.

Anti-Pattern 10 - Not converting production bugs to tests

One of the goals of testing is to catch regressions. As we have seen in antipattern 4, most applications have a “critical” code part where the majority of bugs appear. When you fix a bug you need to make sure that it doesn’t happen again. One of the best ways to enforce this is to write a test for the fix (either unit or integration or both).

Bugs that slip into production are perfect candidates for writing software tests

- they show a lack of testing in that area as the bug has already passed into production

- if you write a test for these bugs the test will be very valuable as it guards future releases of the software

I am always amazed when I see teams (that otherwise have a sound testing strategy) that don’t write a test for a bug that was found in production. They correct the code and fix the bug straight away. For some strange reason a lot of developers assume that writing tests is only valuable when you are adding a new feature only.

This could not be further from the truth. I would even argue that software tests that stem from actual bugs are more valuable than tests which are added as part of new development. After all you never know how often a new feature will break in production (maybe it belongs to non-critical code that will never break). The respective software test is good to have but its value is questionable.

On the other hand the software test that you write for a real bug is super valuable. Not only it verifies that your fix is correct, but also ensures that your fix will always be active even if refactorings happen in the same area.

If you join a legacy project that has no tests this is also the most obvious way to start getting value from software testing. Rather than attempting to guess which code needs tests, you should pay attention to the existing bugs and try to cover them with tests. After a while your tests will have covered the critical part of the code, since by definition all tests have verified things that break often. One of my suggested metrics embodies the recording of this effort.

The only case where it is acceptable to not write tests is when bugs that you find in production are unrelated to code and instead stem from the environment itself. A misconfiguration to a load balancer for example is not something that can be solved with a unit test.

In summary, if you are unsure on what code you need to test next, look at the bugs that slip into production.

Anti-Pattern 11 - Treating TDD as a religion

TDD stands for Test Driven Development and like all methodologies before it, it is a good idea on paper until consultants try to convince a company that following TDD blindly is the only way forward. At the time of writing this trend is slowly dying but I decided to mention it here for completeness (as the enterprise world is especially suffering from this anti-pattern).

Broadly speaking when it comes to software tests:

- you can write tests before the respective implementation code

- you can write tests at the same time as the implementation code

- you can write tests after the implementation code

- you can write 0 tests (i.e. never) for the implementation code

One of the core tenets of TDD is always following option 1 (writing tests before the implementation code). Writing tests before the code is a good general practice but is certainly not always the best practice.

Writing tests before the implementation code implies that you are certain about your final API, which may or may not be the case. Maybe you have a clear specification document in front of you and thus know the exact signatures of the code methods that need to be implemented. But in other cases you might want to just experiment on something, do a quick spike and work towards a solution instead of a solution itself.

For a more practical example, it would be immature for a startup to follow blindly TDD. If you work in a startup company you might write code that will change so fast that TDD will not be a big help. You might even throw away code until you get it “right”. Writing tests after the implementation code, is a perfectly valid strategy in that case.

Writing no tests at all (option 4) is also a valid strategy. As we have seen in anti-pattern 4 there is code that never needs testing. Writing software tests for trivial code because this is the correct way to “do TDD” will get you nowhere.

The obsession of TDD zealots on writing tests first no matter the case, has been a huge detriment to the mental health of sane developers. This obsession is already documented in various places so hopefully I don’t need to say anything more on the topic (search for “TDD is crap/stupid/dead”).

At this point I would like to admit that several times I have personally implemented code like this:

- Implementing the main feature first

- Writing the test afterwards

- Running the test to see it succeed

- Commenting out critical parts of the feature code

- Running the test to see it fail

- Uncommenting feature code to its original state

- Running the test to see it succeed again

- Commiting the code

In summary, TDD is a good idea but you don’t have to follow it all the time. If you work in a fortune 500 company, surrounded by business analysts and getting clear specs on what you need to implement, then TDD might be helpful.

On the other hand if you are just playing with a new framework at your house during the weekend and want to understand how it works, then feel free to not follow TDD.

Anti-Pattern 12 - Writing tests without reading documentation first

A professional developer is one who knows the tools of the trade. You might need to spend extra time at the beginning of a project to learn about the technologies you are going to use. Web frameworks are coming out all the time and it always pays off to know all the capabilities that can be employed in order to write effective and concise code.

You should treat software tests with the same respect. Because several developers treat tests as something secondary (see also Anti-pattern 9) they never sit down to actually learn what their testing framework can do. Copy-pasting testing code from other projects and examples might seem to work at first glance, but this is not the way a professional should behave.

Unfortunately this pattern happens all too often. People are writing several “helper functions” and “utilities” for tests without realizing that their testing framework already offers this function either in a built-in manner or with the help of external modules.

These utilities make the tests hard to understand (especially for junior developers) as they are filled with in-house knowledge that is non transferable to other projects/companies. Several times I have replaced “smart in-house testing solutions” with standard off-the-shelf libraries that do the same thing in a standardized manner.

You should spend some time to learn what your testing framework can do. For example try to find how it can work with:

- parameterized tests

- mocks and stubs

- test setup and teardown

- test categorization

- conditional running of tests

If you are also working on the stereotypical web application you should do some minimal research to understand what are the best practices regarding

- test data creators

- HTTP client libraries

- HTTP mock servers

- mutation/fuzzy testing

- DB cleanup/rollback

- load testing and so on

There is no need to re-invent the wheel. The sentence applies to testing code as well. Maybe there are some corner cases where your main application is indeed a snowflake and needs some in-house utility for the core code. But I can bet that your unit and integration tests are not special themselves and thus writing custom testing utilities is a questionable practice.

Anti-Pattern 13 - Giving testing a bad reputation out of ignorance

Even though I mention this as the last anti-pattern, this is the one that forced me to write this article. I am always disappointed when I find people at conferences and meetups who “proudly” proclaim that all tests are a waste of time and that their application works just fine without any testing at all. A more common occurrence is meeting people who are against a specific type of testing (usually either unit or integration) like we have seen in anti-patterns 1 or 2

When I find people like this, it is my hobby to probe them with questions and understand their reasons behind hating tests. And always, it boils down to anti-patterns. They previously worked in companies where tests were slow (Anti pattern 7), or needed constant refactoring (Antipattern 5). They have been “burned” by unreasonable requests for 100% code coverage (Anti-pattern 6) or TDD zealots (Antipattern 11) that tried to impose to the whole team their own twisted image of what TDD means.

If you are one of those people I truly feel for you. I know how hard it is to work in a company that has bad habits.

Bad experiences of testing in the past should not clutter your judgment when it comes to testing your next greenfield project. Try to look objectively at your team and your project and see if any of the anti-patterns apply to you. If yes, then you are simply testing in the wrong way and no amount of tests will make your application better. Sad but true.

It is one thing for your team to suffer from bad testing habits, and another to mentor junior developers declaring that “testing is a waste of time”. Please don’t do the latter. There are companies out there that don’t suffer from any of the anti-patterns mentioned in this article. Try to find them!

Go back to contents, contact me via email or find me at Twitter if you have a comment.